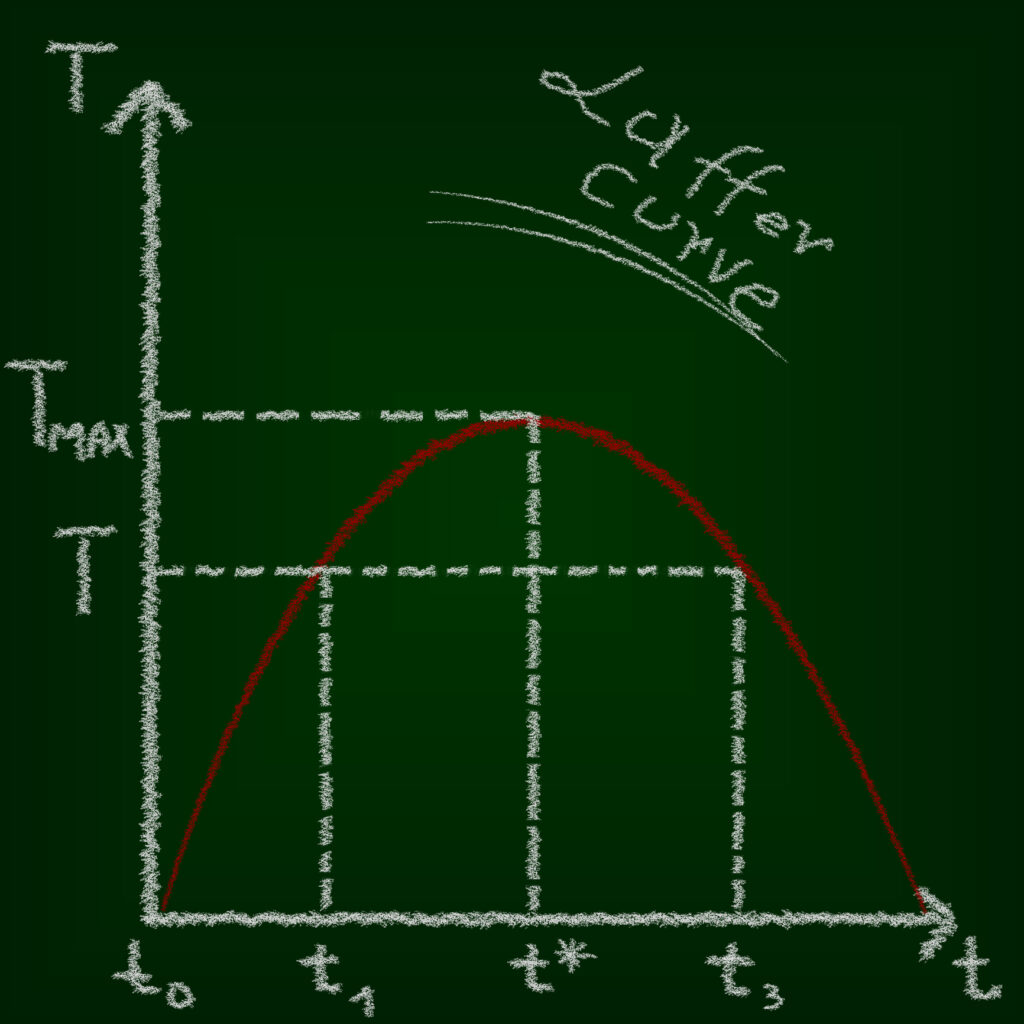

In the lexicon of public economics, the term “Laffer Effect” or “Laffer Curve” is widely known. It illustrates a theoretical relationship between tax rates and tax revenue, suggesting that beyond a certain threshold, raising tax rates may reduce total revenue because disincentives to work, invest, or produce take effect. The “Laffer Effect,” as used in various contexts, captures the broader concept: that an action intended to stimulate or control a system may, past a certain point, generate diminishing or adverse outcomes. In this article, we delve into a refined definition of the “Laffer Effect,” and more importantly, explore how this idea applies to supply‑chain operations.

At its core, the Laffer Effect posits diminishing or even negative returns when pushing a lever too far, whether that lever is taxation, regulation, production capacity, or workflow intensity. While this principle is easier to grasp in fiscal policy, it has powerful implications in the realm of supply chain: from procurement to production, inventory management to last‑mile delivery. By analyzing the concept through a supply‑chain lens, we uncover how intuitive interventions may yield counterintuitive disruptions when they cross optimal thresholds.

Defining the Laffer Effect

Classic Tax-Origin Context

The original idea behind the Laffer Curve comes from economic theory: a government’s revenue depends not only on how high tax rates are, but also on how those rates influence behavior. At a 0% tax rate, revenues are zero; likewise, at a 100% rate, no one has an incentive to earn taxable income, so revenue is again zero. Between these extremes lies an optimal tax rate that maximizes revenue. The “curve” is conceptual, its precise shape varies by economy, context, and individual behavior.

The Generalized Laffer Effect

Beyond taxation, the “Laffer Effect” describes situations in many systems where increasing effort, burden, or restriction beyond a certain point yields progressively less benefit, and can even reverse gains. For instance:

- Over-scheduling production might increase output up to a point, but beyond that point, burnout, equipment breakdowns, or quality issues reduce effective output.

- Heavy regulation or oversight may stabilize operations up to a point, but excessive bureaucracy leads to delays, miscommunication, and lost flexibility.

In this broader sense, the Laffer Effect is a warning about over-optimization in one dimension at the expense of systemic performance.

Supply Chain Fundamentals That Intersect the Laffer Effect

To apply the Laffer Effect meaningfully, it helps to outline key components of supply chains where pushing increases or constraints too far can be counterproductive.

- Procurement and Sourcing

Increasing volume discounts, negotiating more frequent deliveries, or squeezing suppliers for lower prices can yield benefits, but overdo it, and suppliers may cut corners, delay deliveries, or refuse to work. - Production and Manufacturing

Maximizing utilization of factory capacity can reduce per‑unit cost, up to a point. Overutilization may lead to breakdowns, maintenance issues, accidents, or lower quality due to fatigue. - Inventory Management

Holding inventory buffers guards against variability. But too much inventory ties up capital, increases warehousing cost, escalates shrinkage, and may lead to obsolescence. - Transportation and Logistics

Compressing lead times or pushing for faster shipping saves time, but premium freight costs, stresses carriers, or leads to mis‑routing may escalate cost or risk. - Labor and Workforce Scheduling

Extending shifts or compressing staff layers may boost throughput temporarily, but continuous overwork leads to fatigue, errors, absenteeism, and turnover. - Information Flow and Oversight

Over‑monitoring, excessive KPIs, or micromanagement can stifle agility, confuse staff, or generate friction in operations. - Supplier–Buyer Contracts and Incentives

Offering bonus incentives for early delivery or penalizing delay can motivate performance, but if set unrealistically, these terms may encourage risky behavior or breach of contract.

In each area, pushing an increase, like production, inventory, oversight, can help up to a point, then begin to degrade performance. That’s the essence of the Laffer Effect in supply‑chain operations: there is an optimal level of each lever, beyond which benefits diminish or reverse.

Illustrative Examples of the Laffer Effect in Supply Chain

Let’s explore several scenarios illustrating how the Laffer Effect plays out in real‑world supply‑chain contexts.

Production Overtime Overreach

A manufacturing plant ramps up production by adding overtime shifts to meet urgent orders. Initially, output increases and revenue grows. However, as overtime accumulates:

- Workers fatigue, reducing efficiency and raising injury risk.

- Equipment operates continuously, increasing breakdowns and downtime.

- Quality control errors rise.

At some point, added overtime yield negligible net gains, or even a decline. Productivity per hour falls; rework consumes capacity; emergency repairs reduce availability. The Laffer Effect manifests: more effort yields less effective output, or even negative net gain.

Excess Inventory Buffer

To prevent stockouts, a distributor expands warehouses and significantly increases safety stock. Initially, fill rates improve and service levels stabilize. But beyond a certain buffer volume:

- Inventory holding costs balloon (storage, insurance, spoilage).

- Capital is tied up rather than reinvested.

- Old inventory obsolesces (especially for electronics, perishables).

- Picking accuracy decreases due to volume and complexity.

Thus, while an inventory buffer helps to a point, pushing it too far hurts.

Procurement Pressure on Suppliers

A retailer demands just‑in‑time deliveries and imposes heavy penalties for delays while squeezing margin for suppliers. To satisfy volume and avoid penalties, suppliers may:

- Thin their margin so low that they cut corners.

- Skimp on quality, workforce, or safety.

- Favor other buyers, deprioritizing the relationship.

- Eventually, break down or pass cost back to buyer.

The increased pressure initially reduces cost and improves flow but ultimately corrodes reliability and quality.

Over-Micromanagement of Logistics

A logistics manager implements tight KPIs, requiring every delivery to be tracked, logged, and micro-coordinated multiple times per hour. In the short term, accountability rises. But soon:

- Drivers become overwhelmed by frequent check‑ins.

- Dispatchers spend more time recording data than managing routes.

- The overhead outweighs coordination benefit.

- Delays or miscommunication escalate.

Too much oversight becomes counterproductive.

Why the Laffer Effect Happens in Supply Chains

System Complexity and Interdependencies

Supply chains involve many interconnected moving parts: people, machines, data, flows, suppliers, regulations, markets. Pushing one parameter too far can have far-reaching consequences: overworked staff make mistakes, stressed suppliers fail, forklifts break, and orders misroute. The Laffer Effect arises because systems are not linear and simple: they are complex and adaptive.

Human and Organizational Limits

People have physical, cognitive, and motivational limits. Workers get tired. Managers get overwhelmed. Organizations bound by rules and culture can only absorb so much change. Pushing beyond these limits yields inefficiencies.

Resource Degradation and Breakdown

Equipment wears, materials degrade, and infrastructure fails. Pushing utilization beyond thresholds accelerates wear and causes breakdowns, leading to downtime that exceeds the gains of over‑utilization.

Escalating Costs and Diminishing Returns

Every additional unit of buffer, overtime, or inspection yields less marginal gain. Meanwhile, costs, monetary, cognitive, and physical, accrue exponentially. Eventually, the cost exceeds the marginal benefit.

Behavioral Backlash

Under pressure, suppliers and workers do what they must to survive, even if it conflicts with your contract or values. Quality issues, corner-cutting, and deviation become common when demands are unrealistic. Initially unseen, the fallout appears later.

Measuring and Locating the Laffer Point

Understanding where that inflection point lies, the “sweet spot” beyond which performance declines, is vital. Key methods include:

Data Analytics and Process Mapping

- Track productivity metrics as overtime hours increase.

- Monitor quality and defect rates versus production volume.

- Evaluate inventory turnover, holding cost, and obsolescence trade‑offs.

- Use dashboards to visualize nonlinear relationships.

By plotting performance vs. lever level (e.g. utilization vs. error rate), managers can identify where returns diminish.

Pilot‑Scale Experimentation

- Introduce changes in small, controlled batches (e.g. add one overtime shift first).

- Observe effects before scaling further.

- Compare against control groups.

Feedback Loops and Continuous Monitoring

- Integrate real-time feedback (quality reports, supplier delivery data, employee surveys).

- Watch early signs of stress, rising defects, drop in morale, excuses, and turnover.

- Stop or reverse before the system breaks.

Scenario Planning and Simulation

- Use digital twins or simulation software to model stress points.

- Run “what‑if” scenarios under different demand, labor, or inventory settings.

- Pre‑empt thresholds rather than fail in real life.

Tactical Interventions to Respect the Laffer Effect

Recognizing that more is not always better, supply‑chain leaders can adopt strategies that avoid pushing past the performance peak, and even flatten the declining slope.

Balanced Workload and Flexible Capacity

- Instead of sustained overtime, use flexible staffing, temporary workers, shifts rotation.

- Invest in preventive maintenance so equipment stays reliable under peak use.

- Cross-train staff to distribute workload and reduce fatigue.

Dynamic Inventory Policies

- Use demand forecasting to adjust safety stock levels dynamically.

- Implement just-in-time in coordination with reliable suppliers, don’t rely on static high buffers.

- Employ vendor-managed inventory when appropriate to shift holding risk.

Collaborative Supplier Relationships

- Build partnerships rather than adversarial contracts.

- Share demand visibility so suppliers can plan and scale.

- Offer volume-based incentives, but within realistic targets.

- Co‑invest in capacity or quality improvement rather than pressure with penalties.

Lean and Agile Logistics

- Emphasize flexible routing, load consolidation, and batch scheduling rather than rush‑only mindset.

- Use automated tracking judiciously, inform, don’t micromanage.

- Empower drivers and dispatchers to solve exceptions with minimal friction.

Human-Centered Management

- Monitor workforce well‑being (stress indicators, turnover intent, absenteeism).

- Use scheduling that considers recovery time and avoids prolonged over‑tension.

- Encourage feedback and allow process improvements from the floor level.

Contingency Planning

- Recognize that pushing one lever too far makes systems brittle. Instead, build redundancy in other areas: alternate suppliers, modal flexibility, extra routing options.

- Prepare to absorb shocks without overstraining any single channel.

Case Scenario (Hypothetical Composite)

Imagine a mid‑sized consumer‑electronics supply chain:

- To meet holiday demand, the firm increases production by 40% through added shifts.

- Warehouse staff are asked to process 150% of usual picking volume; temporary staff are added hastily.

- Safety stock doubles to prevent runouts.

- Logistics team pushes carriers for guaranteed two‑day delivery.

At first, revenue grows, service levels look strong, and leadership feels confident. But by mid‑December:

- Quality control flags defective units rising 5× normal.

- Warehouse injuries increase; picking mistakes spike.

- Inventory carrying costs balloon, cash flow tightens.

- Carriers start delaying shipments or invoicing late for rush lanes.

- Employees burn out; absenteeism and turnover rise.

- Suppliers struggle to keep up with parts demand; they start substituting lower‑grade components.

Performance declines. Profit drops due to rework, returns, expedited freight, excess inventory write‑offs, and lost supplier reliability. The drive to maximize output beyond the system’s sweet spot has backfired, classic Laffer Effect.

Had leadership modeled the risk and incrementally ramped with more buffer for quality, equipment downtime, and labor capacity, they would have avoided the steep drop. Instead of a straight 40% ramp, a phased increase with condition thresholds would preserve both volume and integrity.

Framing the Laffer Effect: A Supply‑Chain Mindset Shift

Recognizing the Laffer Effect in supply chain isn’t just an analytical insight, it requires a shift in leadership mindset:

- From “more is better” to “optimization.” Understand that certain stress points exist; hitting them hurts more than helps.

- From isolated metrics to systemic health. Don’t chase one KPI (e.g. utilization) at the cost of system-wide resilience.

- From short-term bursts to sustainable throughput. Surges must be controlled; crises managed with foresight.

- From punitive control to collaborative adaptation. Suppliers, logistics partners, employees, and technology should be allies in managing peaks, not victims of them.

Benefits of Avoiding the Downside of Laffer Pressure

Rationally avoiding pushing systems into declining-performance zones yields concrete benefits:

- Improved Quality and Consistency

Avoiding fatigue and burnout supports steadier production and fewer defects. - Greater Supplier Reliability

Cooperative load sharing ensures suppliers remain capable and trustworthy. - Healthier Cash Flow

Right‑sizing inventory reduces holding cost and release tied capital. - Reduced Operational Risk

Balanced logistics prevent breakdowns and unpredictable costs. - Enhanced Workforce Morale and Safety

Sustainable work demands reduce accidents and attrition. - Better Visibility and Decision‑Making

Systems aren’t strained, so data remains trustworthy and leaders stay proactive.

Implementing Laffer‑Aware Supply Chain Governance

To anchor the Laffer Effect mindset operationally, companies can embed structures:

Threshold-Based Triggers

- Define clear metrics and pressure thresholds (e.g., max overtime hours, inventory days on hand, production run hours).

- When thresholds approach, automatically halt further increases and trigger alerts.

Cross-Functional “Stress Review Teams”

- Hold regular meetings across procurement, production, quality, logistics, finance, and HR.

- Review stress indicators collectively (quality trends, vendor performance, workforce feedback).

- Decide in real time whether to ease pressure.

Continuous‑Improvement Culture

- Promote frontline suggestions to smooth pressure (e.g., schedule tweaks, ergonomic aids, supplier improvements).

- Value structural resilience over heroic firefighting.

Dynamic Planning Tools

- Use systems that can model the effect of simultaneous changes across departments.

- Simulate impacts before implementing extreme changes.

Future‑Proofing Supply Chains from Laffer Collapse

In an increasingly volatile global environment, subject to shocks like pandemics, geopolitical disruption, and raw‑material scarcity, the risk of unknowingly triggering Laffer-type over-optimization is high. Firms that monitor for, and avoid systemic stress will be better positioned to:

- Absorb shocks without fracturing their chain.

- Pivot strategies quickly with reliable systems intact.

- Scale sustainably over time, rather than burst‑scale collapse.

- Maintain trust with partners and workers under pressure.

Conclusion

The “Laffer Effect,” understood beyond its original tax‑curve context, reveals a powerful warning: in complex systems like supply chains, more is not always better. Whether the lever is overtime, inventory, pressure on suppliers, oversight, or logistics speed, pushing beyond optimal levels risks backfire—slows performance, degrades quality, inflates cost, erodes trust.

Mindful leadership recognizes this non-linear threshold and aims for resilient, adaptive, and balanced operations. By measuring carefully, ramping incrementally, listening to system feedback, and forming collaborative ecosystems, firms can operate near, but not beyond, the tipping point. That’s how supply chains avoid the fall of the Laffer cliff and sustain healthy performance over time.

In summary, applying the “Laffer Effect” lens to supply chain operations reframes emphasis: from maximum push to optimized balance. It invites decision‑makers to chart the curve carefully, stay on the rising slope, and avoid the dangerous fall off the edge.